- English

- Basque

- Spanish

Workshop: What Care Sustains? | A balloon and a diamond. An epilogue

24.02.2022, Centro Huarte, Navarre

Author(s): Mirari Echavarri

We have been educated to respect fear more

than our need for language and definition,

but if we wait in silence for courage to come,

the weight of silence will drown us.

Audre Lorde

I

I set out to write an essay and that activated a problem-creating mechanism which led that very writing to be postponed. Truthfully, the trigger to this all was having accepted the job to create something from the ¿Qué sostienen los cuidados? (What does care support?) conferences, which took place at the Huarte Center over the months of October, November and December 2021. The job is open-ended, but I interpret that what is expected of me, as an artist, is that I give an account of the days with something more than a utilitarian record. And here the mechanism is churning out the first problem: that extra. Something indefinite, indefinable, a touch of a magic wand that turns something already seen into something new.

I’m deciding to start with the simple thing: record the audio from the conferences and then transcribe them, about 15 hours in total. This step, far from solving the problem, entails another, in this case more perceptive one, which is that I have the feeling that the something, pages and pages of things said by others, is already more, much more than what I can offer or say. However, I feel that the strategy of transcribing – of postponing – is not entirely paralysing. I’m hopeful that, by writing the words of the others, I can in-corporate them, and in that process of absorption-digestion, they will become working material.

However, I have a third problem, which is that if I take the subject of the conference seriously, I think I should apply some care to this whole process. For example, I think I should do this without exploiting myself. So no shutting myself in at home all day in front of the computer screen, feeding my anxiety and forcing myself to write. However, I have already set myself several deadlines and missed all of them. As always, I would rather not do it. I imagine turning down the job, but I dare not. That’s why it’s so good when I say no in time. I convince myself that I can't, but at the same time I have to, I need to be able to. The thought of not doing it alleviates my anxiety for a while, but faced with the prospect of not receiving the commission for this job, my anxiety only grows and becomes more aggressive. So I reconsider the third problem and tone down my self-imposed demands. I'm not going to pretend that I can write this without high doses of guilt, laziness, and fear. Nor will I pretend that in return I do not receive some degree of confessional pleasure. These are the parts of my psychological and material patchwork right now. This is the words of those others already claiming their place.

II

How can one name names without over-narrating? Luisa Fuentes Guaza, the facilitator-articulator-backbone of the conference, mentioned the over-narration of care several times. They are assiduously narrated within the institutions, including arts institutions. Or rather, they are named and perhaps over-narrated, and from insisting so much on their signifier, their significance becomes diluted. For Luisa, care is a tailor's drawer, where an enormous amount of different jobs requiring specification accumulates. What they need, she says, is for us to delve into the different natures of these jobs; and we have to name them, put words and material and symbolic conditions to them to make them liveable; to structure a whole legal, political, economic system, so that care does not keep on accumulating in the same ever more precarious bodies, subjected to conditions of slavery and disease. These conferences, without a doubt, shed light on that drawer. And each voice, each body, with its implacable specificity, has helped to turn that morass of hidden jobs into a plot wherein each fibre is discernible, as are the junctions where they intertwine. I do not intend, in this essay, to make each of these fibres and junctions visible. I cannot make a literal translation of what happened there. I can't show that much because I have to show something else.

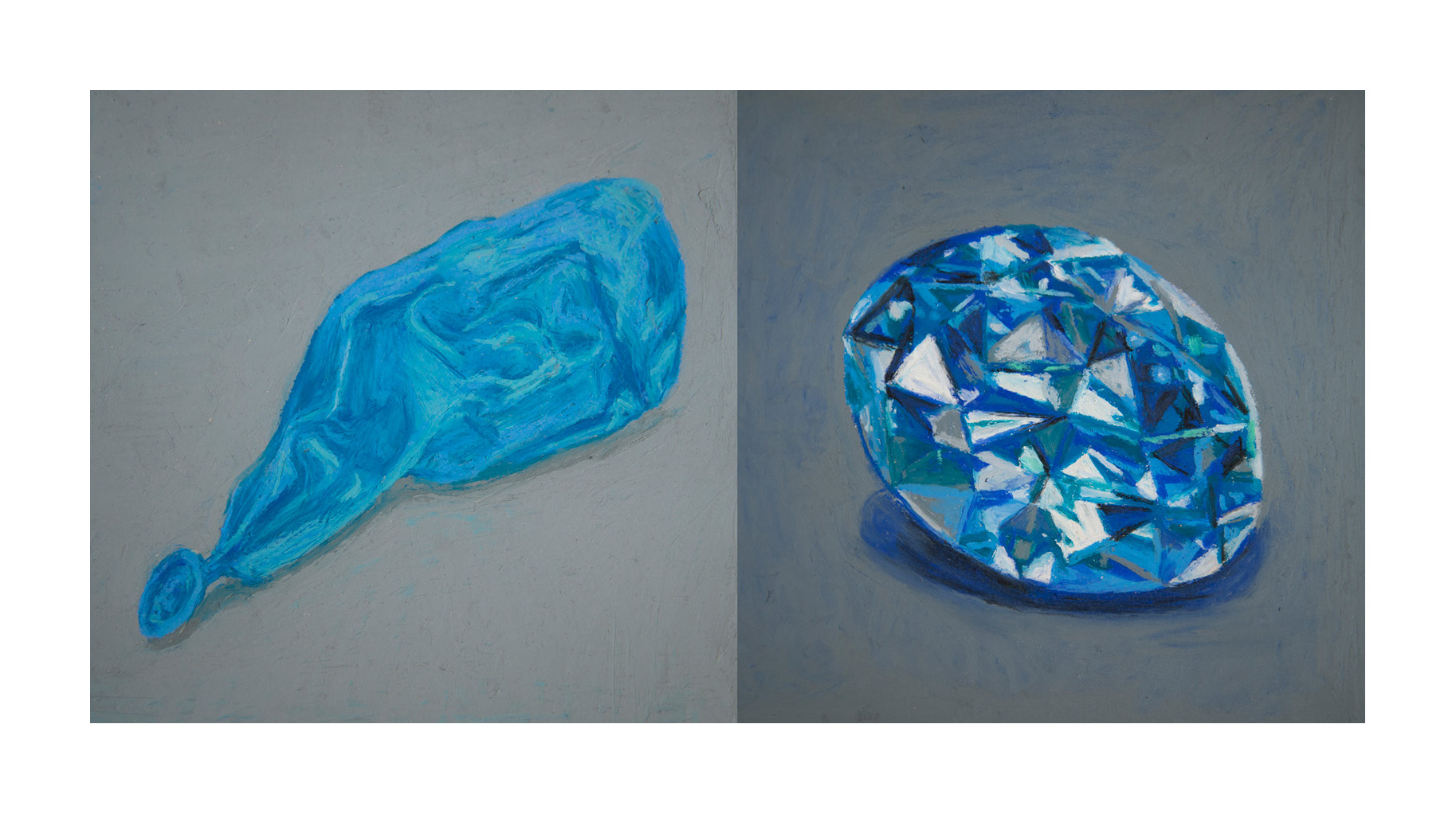

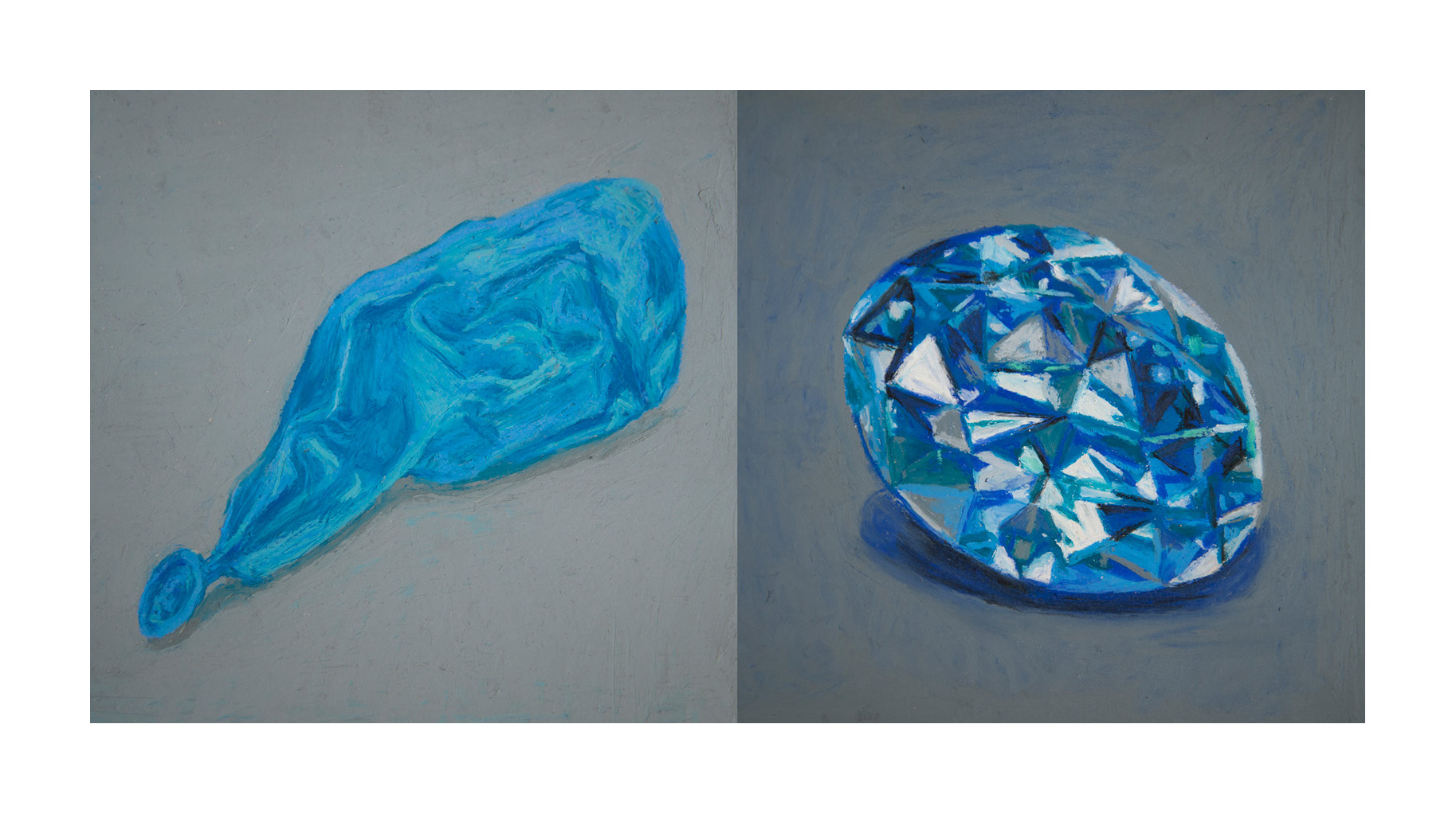

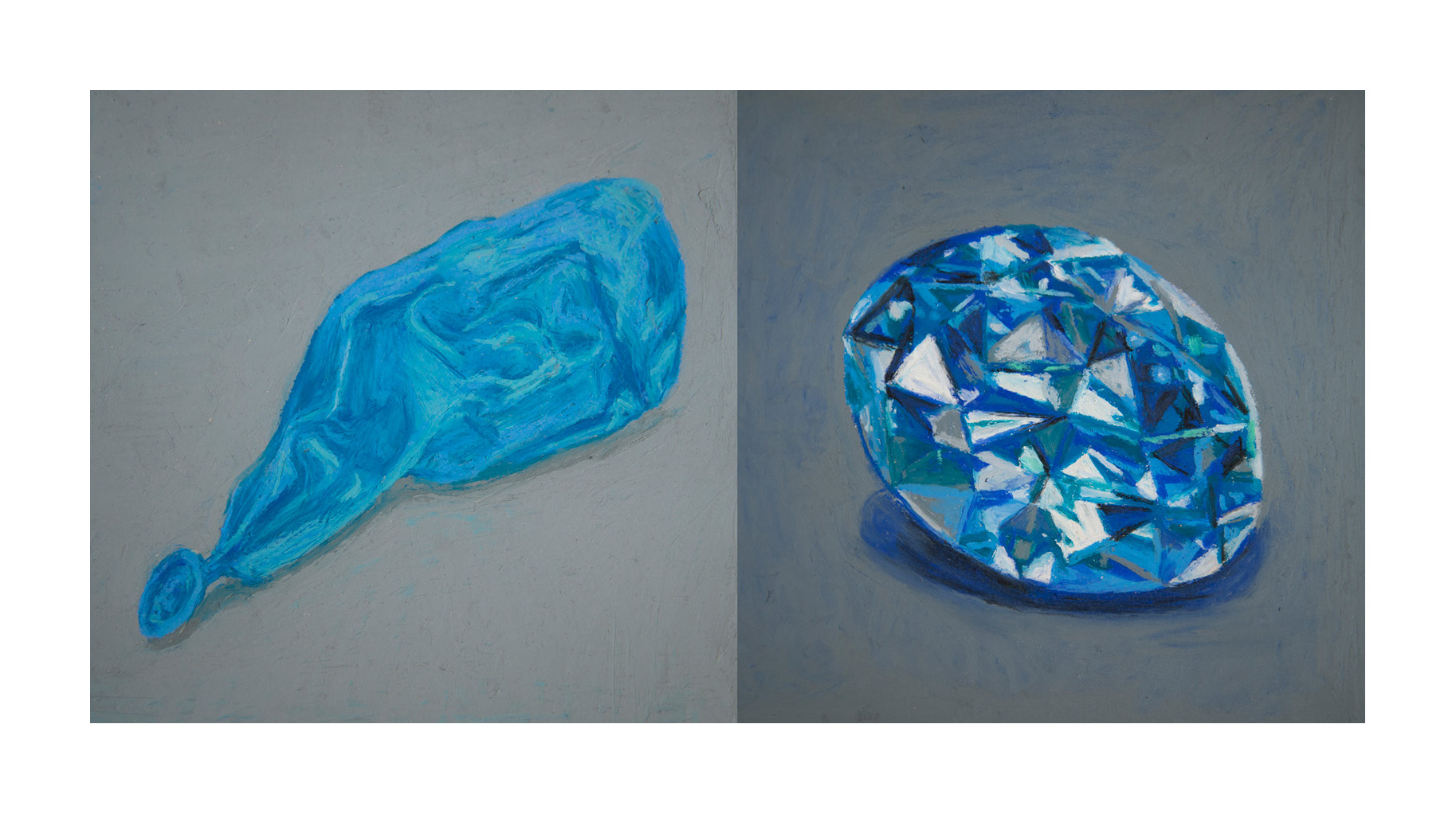

If I don't wrap up this writing, I postpone it, for example, by painting. In this case, painting the words of the others has served a twofold purpose: to calm the anxiety that I get from working, by working. A balloon and a diamond. On the first day Irati Mogollón, spoke of a deflated balloon to describe something very concrete: the rare form that some social movements acquire after having grown very fast and diminished just as quickly. Irati told us that life’s sustainability options are part of everyday life, and that this entails a challenge, because as time passes, the political erotica vanishes and people lose interest, motivation, energy, desire. To procrastinate is sometimes to wish in another direction. As I paint I also think of a tired or sick body, of a body that cares in precarious conditions because it has no other choice.

Then comes another image. That of splendour. Luisa had asked the speakers from the first session to think about the wealth generated by the bodies they care for and Erika Irusta imagined that her body housed diamonds, riches that she was unable to see, because her eyes, her ability to feel proud, and the possibility of letting them be, had been stolen. And she wondered, must we extract our wealth? Does the relationship with wealth in care always have to be extractive? Do I have to produce with it? For Erika, 'plundered plunderer', what the white-colonial-cisheteropatriarchal system does with maternal bodies and the bodies they care for is plunder their many riches, those necessary to sustain life and the continuity of the system itself.

III

June 2020

"With what time I have left, silence doesn’t pay off"

I bought a cane. I did so because I had a hard time walking. I needed it for any distance of more than 100m, to go up and down the stairs at home.

At first I also clung tightly to the table top to get up from the sofa. I leaned on the walls to unload weight from my bad hip.

This happened a little before and a little after the diagnosis: My breast cancer of just eleven years, has metastasised in my bones. My vertebrae, ribs and pelvis are affected.

The cancer is back, this time to stay.

Suddenly last night, insomnia again. It seemed to me that I had to declare war, no actually, to neglect silence and the mind block that have prevented me from writing for so long. Whatever I may have to say.

For example: life and cancer end at the same point.

*

I transcribe my mother's words, too. I took them from a notebook with a green cover and yellowish pages entitled 'Crónica del cáncer' (Cancer journal). My mother had always written diaries, but by then she hadn't done so for quite some time. She had realised that she had been subtly self-censoring everything written —a substrate of nunnish shyness cleaning everything, polishing even the deepest nooks— and then she decided to stop writing. However, getting sick again and rereading Audre Lorde's The Cancer Journals made her start again.

A short time later the cancer advanced to her spinal cord, taking away her mobility and sensitivity from the waist down. She was admitted to the oncology emergency unit and treated with radiotherapy, in addition to chemotherapy. Later on she would be transferred to palliative care until she was able to return home, where she died in the early hours of January 27, 2021.

She left me her words as an inheritance, scattered in a pile of diaries.

*

I sense that no particularly interesting reflection will come out of this journal, or none that have not already been expressed otherwise.

However, I won’t let that be the reason that I remain in silence. It is important that I tell myself that which does not usually fit into everyday conversations, with family or friends, that breaks down the façade of normality for which each day I pay a price.

*

Nor are silences the same. That of Audre Lorde, black woman, poet, feminist, mother, lesbian, lover, warrior, is much more urgent to turn into words than mine: white woman, heterosexual, conformist, survivor of many wars, large and small ... She says, "And, of course, I'm afraid because the transformation of silence into language and action is an act of self-revelation and that always seems fraught with danger."

"We can stay in our safe nooks, mute like bottles, and even then our fear will not wane."

She chose activism as a commitment to language. I am a mute bottle. Mute and unconscious, maybe because I’ve buried my fears so that they won’t reveal anything uncomfortable to me.

I'm tired.

*

October 2020

It had been smelling like sewer for several days.

The bag of pee and its tubes filled with sediment had a bitter effect on my sense of smell. They changed it this afternoon. Finally, a break! I don’t know what we are inside, but it isn’t much to get excited about!

I’m writing freehand. I don’t even know how to hold the notebook anymore. There is no way of adopting a normal posture to write in this soft notebook in bed, it keeps slipping away from me.

*

It is very simple: if the body is weak, your mood wanes.

I resist even that simple premise. I always want to be strong, I always want to be well. I have a hard time accepting these moments of weakness and apathy.

These past few days I felt like I was hitting rock bottom: not wanting anything, worried even because my friends were going to come to take care of me, unable to relax, what bad times I’ve had. I confess it openly: I have had a really bad time, to the point of doubting, of losing confidence in the process...

*

November 2020

Just gratitude, always, despite the confinement of the room and the inconveniences of being hospitalised. What weighed on me the most was a feeling of claustrophobia, as I say, and sadness that was saturating me more and more, every day. Looking at drawings or flowers was no longer relieving me... I just wanted to get out of there. Perhaps that could be interpreted as a sign of recovery. I don’t know. It’s true that in the end I have been stronger. And that now I really appreciate spending the post-chemo phase at home.

*

Meanwhile, my routine hasn't changed much. Keep on assimilating disability, fundamentally, with all the limitations that it entails and, in turn, realise the enormous care with which I am being treated. With the immense gift of love from mine and those close by.

*

January 2021

Every day it is harder for me to write.

*

I have a hard time writing, but silence isn’t paying off. I question my discomfort to name it. If I say anxiety I open another tailor's drawer without a light to shine on it. Nor do I call it depression because I got rid of the productive framework that I could use to face it. It is an ordinary and generalised discomfort that I don’t know where to place, whether inside or outside the body. I think it must be in a liminal, interstitial and mobile space, because when I think that I’ve identified it, it dissolves and escapes, and leaves me shapeless and without splendour. It may have to do with grief, or it may not.

There was something very rewarding about providing care. Without a doubt, accompanying my mother's illness and death has been my privilege. The most urgent form of self-care. And even so, it took many more bodies, money and time to make the process liveable and dignified. In my case, I ended up quitting the job that provided me with a steady income. I wish I had a social support, one that didn’t go through the medical institution, because needing to take care of someone isn’t a disease. I wish that the process to get dependency aid were shorter, as they didn’t arrive on time. It's clear to me that there were avoidable difficulties. And I would’ve liked to have had an alternative to quitting my job, or an alternative to guilt for not being able to handle everything.

But caring has been my privilege. I am only grateful to the bodies that accompanied us through this process that was so beautiful and at the same time so hard, and especially to my mother, Carmen, who took care (of me) her whole life, until the last day, making it so that taking care of her was a pleasure.

IV

Accompany.

Listen.

Be present.

Empty the pee bag.

Change the nappy.

Clean a body that cannot move.

Dress it.

Hydrate it.

Handle a crane to move it.

Massage feet that do not feel.

Be typing fingers that transcribe.

Be her legs.

Clean under the bed.

Clean around it.

Hold the spoon.

Kiss a beloved body.

Kiss a body that dies.

Inject morphine, midazolam, haloperidol.

Hold her hand.

Caress her hand.

Release her hand.

Embrace a dead beloved body.

V

...

Restore dignity and value to care work.

Write the Statute of Care.

Amend the Dependency Law.

Repeal the Aliens Act.

Abolish intern work.

End racist abuse and aggression in Spanish homes.

Differentiate home work from care work.

Draft a specific law for the care work of dependent persons at home.

Guarantee the right of dependent people to decide how they want to be cared for.

Recompense maternal plundering.

Guarantee psycho-emotional support during the postnatal period.

Make amends for plundering migrated bodies.

Create an urban fabric from the bodies they care for and the bodies that need to be cared for.

Implement the Universal Basic Income.

Compensate care.

Extend permits to care for dependent and terminally ill people.

Extend leave for the death of a loved one. Ensure the right to grieve.

Politicise discomfort. Depathologise it.

Reduce bureaucracy.

Work on epic everyday narratives.

Establish the limits of sustaining life.

Work on feminist reciprocity.

Shoulder the struggles of all.

...

Thanks to Luisa, Irati, Erika, María, Irene, Sarah, Mary, Ana, Alexia, Cristina, Gabriela, Paloma, Blanca, Zarys, Lara, Anita and many others, for not settling with silence.

Puxika bat eta diamante bat. Zer eusten dute zaintzek? jardunaldien epilogoa

24.02.2022, Centro Huarte, Nafarroa

Egilea(k): Mirari Echavarri

Beldurrari begirunea izateko hezi gaituzte hizkuntza eta definiziorako gure beharrari baino, baina isilik geratzen bagara ausardia noiz etorriko, isiltasunaren pisuak ito egingo gaitu.

Audre Lorde

I

Testu bat idazteko asmoa dut, baina horrek eragin duen mekanismo-buruhauste-sortzaileak idazketa behin eta berriz atzeratzea ekarri du. Egiaz, 2021eko urrian, azaroan eta abenduan Huarte Zentroan egin ziren Zer eusten dute zaintzek? jardunaldien harira zerbait sortzeko enkarguari baietz esan nionean hasi zen dena. Enkargua irekia den arren, interpretatu dut niregandik, artista naizen aldetik, espero dena jardunaldien inguruko gogoeta egitea dela baina ohiko erregistroa baino zerbait gehiago erabiliz. Eta hona mekanismoaren lehen buruhaustea: gehigarri hori; definitu gabeko eta definitu ezineko zerbait, jasotako zerbait zerbait berri bihurtuko duen makilatxo magikoa.

Bada, zerbait soilarekin hastea erabakitzen dut: jardunaldien audioa grabatu, ondoren transkribatzeko. Guztira, 15 ordu inguru. Baina honek arazoa konpondu beharrean beste bat sortzen du, pertzepziokoa, oraingoan. Zerbait hori, besteek orrialde piloan adierazitakoak, dagoeneko gehiago den sentsazioa dut, nik eskaini edo esan dezakedana baino askoz gehiago. Dena den, transkribatzeko (geroratzeko) estrategiak ez nauela guztiz geldiarazi sentitzen dut. Besteen hitzak idaztean hitz horiek in-korporatu egin ditzakedan eta, xurgatze/digestio prozesu horretan, laneko material bihurtuko diren itxaropena dut.

Baina hirugarren buruhauste bat ere bada: jardunaldien gaia ganoraz jorratuko badut, prozesu osoa nolabait zaindu beharko nukeela uste dut. Esate baterako, hau nire burua esplotatu gabe egin beharko nukeela uste dut. Ez dut egun osoa ordenagailu-pantailaren aurrean pasako, inola ere, antsietatea elikatzen eta nire burua idaztera derrigortzen. Hala ere, ez dut ezarri dudan epemuga bakar bat ere bete. Ohi bezala, nahiago nuke ez egin. Enkarguari ezetz esaten irudikatzen dut nire burua, baina ez naiz ausartzen. Horregatik, ederra da ezetz garaiz esaten dudanean. Ezin dudala sinestarazten diot nire buruari, baina, aldi berean, gai izan behar dut, gai izateko beharra dut. Lana ez egitearen ideiak nire antsietatea arintzen du une batez, baina, enkargua ez dudala kobratuko gogora datorkidanean, handiago eta bortitzago bilakatzen da. Gauzak horrela, hirugarren buruhaustea birplanteatu, eta nire buruari gutxiago eskatzea erabakitzen dut. Ez dut joko hau nabarmen errudun, alfer edota beldur sentitu gabe idatz dezakedala. Eta ez dut joko ere ez dudala, trukean, plazer konfesional apur bat jasoko. Hori da nire bilbatura psikiko-materikoa osatzen duena momentu honetan, honezkero jasanik haien lekua aldarrikatzen duten besteen hitzak diren hori.

II

Nola aipatu zerbait gehiegizko narrazioa egin gabe? Jardunaldien bideratzaile-antolatzaile-eratzaile Luisa Fuentes Guazak hainbatetan aipatu zuen gehiegizko narrazioa egiten dela zaintzei buruz. Erakundeek, baita arte-arlokoek ere, sarritan egiten dute hori Edo, hobeto esanda, aipatzen dituzte eta agian gehiegizko narrazioa egiten dute haiei buruz; adierazlea gehiegi aipatuta, esanahia lausotu egiten da. Luisaren iritziz, zaintzaren saski-naskian lan mordoa metatu da, lan askotarikoak, baina zehazki zein diren espezifikatu behar da. Premiazkoa da, dio, lan horien berariazko ezaugarriak sakonki aztertzea; eta beharrezkoa da izena ematea, hitz zein baldintza material eta sinbolikoak zehaztea, lanak bizigarri bihurtzeko; sistema juridiko, politiko eta ekonomiko oso bat egituratu behar da zaintzak ez daitezen beti gorputz prekarizatuengan pilatu, esklabotza- eta gaixotasun-baldintzen mende dauden horiengan. Ezin ukatuzkoa da jardunaldi hauek argi egin dutela saski-naski horretan, eta ahots bakoitzak, gorputz bakoitzak, bere ezpezifikotasun menderaezinetik, lagundu duela ikusezin egindako lanen mordoiloa askatzen eta hari-zuntza zein elkarren arteko lotura guztiak agerian dituen bilbea sortzen. Testu honekin ez da nire xedea hari-zuntz eta lotura bakoitzari ikusgarritasuna ematea, ezin baitut jardunaldietan gertatutakoaren hitzez-hitzezko itzulpena egin. Ezin dut hainbeste adierazi zeren eta zerbait gehiago adierazi behar dudalako.

Idazketan trabatu egiten banaiz, geroko utzi eta margotzeari ekiten diot. Besteen hitzak margotzeak funtzio bikoitza izan du kasu honetan: lan egiteak eragiten didan antsietatea baretu, nola eta lan eginez. Puxika bat eta diamante bat. Lehenengo jardunaldian, Irati Mogollón puxika hustu bati buruz mintzatu zen zerbait oso zehatza deskribatzeko: zenbait gizarte-mugimenduk hartzen duten forma arraroa, alegia, hazi ziren abiada bizi berean husten direnean. Iratik azaldu zigun bizitzaren iraunkortasunerako aukerak egunerokoan dautzala, eta hori erronka bat dela, denborarekin politikaren erotika hutsaltzen delako eta jendeak interesa, motibazioa, energia eta desioa galtzen dituelako. Geroratzea, batzuetan, beste leku baterantz desiratzea da. Margotzen dudan bitartean, gorputz eri edo akitu batengan pentsatzen dut, beste erremediorik ez duelako baldintza eskasetan zaintzen duen gorputz batengan.

Jarraian, beste irudi bat ikusten dut. Distirarena. Luisak lehenengo jardunaldiko hizlariei eskatu zien zaintzen duten gorputzek sortzen dituzten aberastasunen inguruan pentsatzea, eta Erika Irustak imajinatu zuen bere gorputzak diamante batzuk gordetzen zituela baina ez zela gai aberastasun horiek ikusteko, zeren eta begiak, harro sentitzeko gaitasuna eta haiek beren horretan uzteko aukera ostu dizkiotelako. Eta bere buruari galdetzen zion: gure aberastasunak erauzi behar al ditugu? Zaintzari lotutako aberastasunekin dugun harremanak beti izan behar al du erauzketa-harremana? Behartuta al nago haiekin zerbait ekoiztera? Erikaren aburuz, ‘espoliatutako espoliatzailea’, zera egiten du sistemak –zuri-kolonial-zisheteropatriarkalak– ama-gorputzekin eta gorputz zaintzaileekin: haien aberastasun ugariak espoliatu, bizia sostengatzeko zein sistemak berak aurrera jarraitzeko behar adina baliatuz.

III

2020ko ekaina

“Geratzen zaidan denborarako, ez du merezi isilik egotea”

Makulua erosi nuen. Ibiltzea kostatzen zitzaidalako erosi nuen. 100 metro baino gehiagoko distantzietarako behar nuen, eta etxeko eskailerak igotzeko eta jaisteko.

Hasieran, sofatik altxatzeko, gogor eutsi behar nion mahaiaren gainari. Hormetan bermatzen nintzen, aldaka gaixoaren pisua arintzeko.

Diagnostikoa baino zertxobait lehenago eta zertxobait geroago gertatu zen hori: Duela hain justu 11 urteko bularreko minbiziaren metastasia hezurretara iritsi da. Ornoak, saihetsak eta pelbisa eragin ditu.

Minbizia itzuli egin da, betirako oraingo honetan.

Bart, tupustean, insomnioa berriz ere. Isiltasunari gerra deklaratu behar niola iruditu zitzaidan, edo, hobe esanda, haren nagikerian bere kasa utzi, luzaroan idazten utzi ez didan blokeoari. Edozer dela esan behar dudana.

Adibidez: biziak eta minbiziak helmuga bera dute.

*

Nire amaren hitzak ere transkribatzen ditut. “Crónica del cáncer (Minbiziaren kronikak)” izena duen azal berdeko eta orrialde horixketako koaderno batetik atera ditut. Amak betidanik zuen egunerokoak idazteko ohitura, baina aspaldi zuen utzia ordurako. Bere idazki guztiak sotilki autozentsuratzen zituela jabetu zen –lotsa puritano batek dena garbitzen zuen, zirrikiturik ilunenak ere distirarazten zituen– eta idazteari utzi zion. Baina berriz gaixotzeak eta Audre Lorde-n Minbiziaren egunerokoak irakurtzeak idazteari berrekitera bultzatu zuten.

Hortik gutxira, minbiziak bizkarrezur-muina hartu, eta gerritik beherako sentikortasuna eta mugitzeko gaitasuna kendu zizkion. Larrialdi onkologikoen unitatean ospitaleratu zuten, eta erradioterapia eta kimioterapia eman zizkioten. Ondoren, zainketa aringarrietako unitatera eraman zuten; gero, etxera itzuli zen, eta bertan zendu zen, 2021eko urtarrilaren 27ko goizaldean.

Haren hitzak jaso nituen oinordetzan, makina bat egunerokotan sakabanatuta.

*

Nago koaderno honetatik ez dela aterako gogoeta interesgarririk, ezta lehenago adierazi ez denik ere.

Eta, hala ere, ez dut isilik jarraituko. Garrantzitsua da familiarekin eta lagunekin ditudan eguneroko solasaldietan txokorik izaten ez duena nire buruari esatea, egunero ordaintzen dudan normaltasun-itxura desmuntatuko duen hori.

*

Isiltasun guztiak ere ez dira berdinak. Askoz premiazkoagoa da Audre Lorden –emakume beltz, poeta, feminista, ama, lesbiana, amorante eta gerlaria– isiltasunari hitzak ematea nireari –emakume zuri, heterosexual, normatibo, gerra handi eta txiki askotatik bizirik aterea– baino. Honela dio hark: “Eta, jakina, beldur naiz, isiltasuna hizkuntza eta ekintza bilakatzeak gure burua ezagutzeko egintza bat dakarrelako, eta horrek arriskuak dakartzala dirudi beti”.

“Gure txoko seguruetan gera gaizteke, botilak bezain mutu, eta, hala ere, beldurra ez da kikilduko”.

Aktibismoa hautatu zuen hark hizkuntzarekiko konpromiso gisa. Ni botila mutua naiz. Mutua eta inkontzientea, ez ote ditut nire beldurrak lurperatu kontu deserosoak azalera ez diezazkidatela.

Nekatuta nago.

*

2020ko urria

Egun batzuk neramatzan gandola-usaina nabaritzen.

Ditxosozko pixa-poltsa, sedimentuz betetako tutuak, usaimena saminduta nuen. Arratsaldean aldatu didate, azkenik. Hori bai lasaitasuna! Ez dakit zer garen barrutik, baina ez nuke ilusio handirik egingo!

Pultsuan idazten dut. Ez dakit koadernoa nola kokatu ere jadanik. Ez dago modurik koaderno bigun honetan idazteko postura onik ohean hartzeko, osorik labaintzen baitzait.

*

Oso erraza da: gorputza ahul badago, adoreak behera egiten du.

Bada, nik premisa erraz-erraz horri ere aurre egiten diot. Beti egon nahi dut adoretsu, beti egon nahi dut ongi. Nekez onartzen ditut ahulezia- eta apatia-une horiek.

Azkeneko egunetan behea jotzen nuela sentitu dut: ez nuen ezertarako gogorik, kezkatuta nengoen lagunak ni zaintzera etorriko zirelako, ez nintzen erlaxatzeko gauza, une oso latzak pasa ditut. Aho betean aitortzen dut: oso gaizki pasa dut, hain gaizki ezen zalantzan, prozesuan konfiantza galtzen hasi bainaiz.

*

2020ko azaroa

Esker onak besterik ez, beti, logelatik atera ezinik egotea eta ospitaleratzearen eragozpenak gorabehera. Sentsaziorik astunena, esan bezala, klaustrofobia izan da, eta tristura, gero eta gehiago blaitzen ninduena egunak pasa ahala. Ezin arindu, ez marrazkiei begiratuz, ez loreei... handik atera baino ez nuen nahi. Susperraldiaren seinale izan liteke hori? Ez dakit. Egia da azkenerako indartsuago sentitu naizela. Eta orain oso eskertuta nagoela kimioaren ondokoa etxean pasa dezakedalako.

*

Bitartean, nire errutina ez da asko aldatu. Desgaitasuna neureganatzen jarraitu, gehien bat, horrek dakartzan muga guztiak asimilatuz eta, aldi berean, tratatzen nauten modu maitekorraz jabetuz. Nire senideen eta gertukoen maitasuna opari aparta dela jabetuz.

*

2021eko urtarrila

Gero eta zailagoa zait idaztea.

*

Idaztea zaila zait, baina ez du merezi isilik geratzea. Nire ondoezari galdetzen diot, izena jarri ahal izateko. Antsietatea esaten badut, beste saski-naski bat irekiko dut, baina argiztatzeko argirik gabe. Depresioa ere ez dut deituko, hura antzemateko ekoizpen-esparrutik aldendu naizelako dagoeneko. Ondoeza arrunt eta orokortu bat da, eta ez dakit gorputzaren barrualdean ala kanpoaldean den. Uste dut espazio liminal, interstizial eta mugikor batean dagoela, desegin eta ihes egiten duelako identifikatu dudala uste bezain pronto, ni formagabe, distiragabe utzita. Doluarekin zerikusia izan lezake, edo ez.

Zaintzak oso alde atsegina zuen. Amari laguntzea gaixotasun- eta heriotza-prozesuan nire pribilegioa izan da, zalantzarik gabe. Autozainketa-modurik premiazkoena. Eta, hala ere, askoz ere gorputz gehiago, dirua eta denbora behar izan ditugu prozesua bizigarri eta duin egiteko. Nire kasuan, lana utzi nuen, diru-sarrera egonkorrak galduta. Sostengu soziala sentitu nuen faltan, osasun-erakundeena ez den bat, norbait zaindu behar izatea ez baita gaixotasuna. Faltan sentitu nuen mendetasunerako laguntzen izapideak laburragoak izatea, ez baitziren garaiz iritsi. Argi dut zailtasun batzuk saihesteko modukoak izan zirela. Eta gustatuko litzaidake beste hautabide bat eduki izana, lana ez uzteko, edo dena egiteko gai ez izateak sorrarazitako errua ez sentitzeko.

Baina zaintzea nire pribilegioa izan da. Esker onak baino ez ditut hain prozesu eder eta zail honetan lagundu diguten gorputz guztientzat. Eta batez ere nire amarentzat, Carmen, bere bizitza osoan eta azken egunera arte zaindu (ninduelako) zuelako, bera zaintzea plazer bilakatuta.

IV

Laguntzea.

Entzutea.

Presente egotea.

Pixa-poltsa hustea.

Pixoihalak aldatzea.

Mugitu ezin den gorputz bat garbitzea.

Janztea.

Hidratatzea.

Lekualdatzeko garabi bat erabiltzea.

Sentsaziorik ez duten oinei masajea ematea.

Transkribatzen duten hatz tekla-jotzaile izatea.

Haren hankak izatea.

Ohe azpian garbitzea.

Inguruan garbitzea.

Koilarari eustea.

Maite duzun gorputz bati musu ematea.

Hiltzen ari den gorputz bati musu ematea.

Morfina, midazolam eta haloperidol txertatzea.

Eskutik heltzea.

Eskua laztantzea.

Eskua askatzea.

Maite duzun gorputz hil bat besarkatzea.

V

…

Zaintza-lanei duintasuna eta balioa itzultzea.

Zaintzaren Estatutua idaztea.

Mendetasun Legea aldatzea.

Atzerritarrei buruzko Legea indargabetzea.

Barneko langileen lana abolitzea.

Espainiako etxeetan gertatzen diren eraso eta abusu arrazistekin amaitzea.

Etxeko lanen eta zaintza-lanen artean bereiztea.

Mendetasuna duten pertsonak etxean zaintzeko lanei buruzko lege berezi bat idaztea.

Mendetasuna duten pertsonek nahi duten zaintza mota aukeratzeko eskubidea bermatzea.

Amei egindako espolioa itzultzea.

Erdiberriaroan laguntza psikoafektiboa bermatzea.

Gorputz migratzaileei espoliatutakoagatik kalteak ordaintzea.

Hiri-bilbe bat sortzea hala zaintzen duten gorputzez nola zaintzak behar dituzten gorputzez osatua.

Oinarrizko Errenta Unibertsala ezartzea.

Zaintza-lanak ordaintzea.

Mendetasuna duten pertsonak zein gaixo terminalak zaintzeko baimenak luzatzea.

Maite dugun norbaiten heriotzagatiko baimenak luzatzea. Dolurako eskubidea bermatzea.

Ondoeza politizatzea. Despatologizatzea.

Burokrazia murriztea.

Eguneroko kontakizun epikoak lantzea.

Bizia sostengatzeko mugak zehaztea.

Elkarrekikotasun feminista lantzea.

Emakume guztien borrokei gorputza ematea.

…

Eskerrik asko, Luisa, Irati, Erika, María, Irene, Sarah, Mary, Ana, Alexia, Cristina, Gabriela, Paloma, Blanca, Zarys, Lara, Anita eta abar, isiltasunarekin ez konformatzeagatik.

Un globo y un diamante. Un epílogo para ¿Qué sostienen los cuidados?

24.02.2022, Centro Huarte, Navarra

Autoría: Mirari Echavarri

Hemos sido educadas para respetar más al miedo

que a nuestra necesidad de lenguaje y definición,

pero si esperamos en silencio a que llegue la valentía,

el peso del silencio nos ahogará.

Audre Lorde

I

Me he propuesto escribir un texto, y esto ha activado un mecanismo-hacedor-de-problemas que ha provocado que la escritura se vaya posponiendo. En realidad, el detonante de todo ha sido aceptar el encargo de crear algo a partir de las jornadas ¿Qué sostienen los cuidados? llevadas a cabo en el Centro Huarte durante los meses de octubre, noviembre y diciembre de 2021. El encargo es abierto, pero yo interpreto que lo que se espera de mí, como artista, es que dé cuenta de las jornadas con algo más que un registro al uso. Y aquí el mecanismo lanza el primer problema: ese extra; algo indefinido, indefinible, un toque de varita mágica que convierta algo dado en algo nuevo.

Decido empezar con el simple algo: registrar las jornadas en audio y después transcribirlas, unas 15 horas en total. Esta acción, lejos de resolver el problema, genera otro nuevo, en este caso perceptivo, y es que tengo la sensación de que el algo, páginas y páginas de cosas dichas por otras, ya es más, mucho más de lo que yo pueda ofrecer, decir. Sin embargo, siento que la estrategia de transcribir –de postergar– no es del todo paralizante. Tengo la esperanza de que, al escribir las palabras de las otras, pueda in-corporarlas, y en ese proceso de absorción-digestión, se conviertan en material de trabajo.

Pero aún se me plantea un tercer problema, y es que, si me tomo en serio el tema de las jornadas, creo que debería aplicar cierto cuidado a todo el proceso. Por ejemplo, pienso que debería hacer esto sin autoexplotarme. Nada de pegarme en casa todo el día delante de la pantalla del ordenador, alimentando mi ansiedad y forzándome a escribir. Sin embargo, ya me he puesto varios deadlines y los he fallado todos. Como siempre, preferiría no hacerlo. Me imagino rechazando el encargo, pero no me atrevo. Por eso, qué bien cuando digo que no a tiempo. Me convenzo de que no puedo, pero a la vez tengo que, necesito poder. La idea de no hacerlo alivia mi ansiedad por un momento, pero frente a la perspectiva de no cobrar el encargo, se vuelve más grande, más agresiva. Así que reconsidero el tercer problema y bajo las exigencias autoimpuestas. No voy a pretender que puedo escribir esto sin altas dosis de culpa, de pereza, de miedo. Tampoco voy a pretender que a cambio no reciba cierto grado de placer confesional. Esto es lo que conforma mi entramado psíquico-matérico ahora mismo, esto que ya son las palabras de las otras reclamando su lugar.

II

¿Cómo nombrar sin sobrenarrar? Luisa Fuentes Guaza, la facilitadora-articuladora-vertebradora de las jornadas, nombró varias veces la sobrenarración de los cuidados. Desde las instituciones, también las del arte, se narran con asiduidad. O más bien se nombran y quizás se sobrenombran, y de tanto insistir en el significante, el significado se vuelve difuso. Para Luisa, los cuidados son un cajón de sastre donde se acumula una cantidad ingente de trabajos diversos que necesitan especificación. Lo que necesitan, dice, es que ahondemos en las distintas naturalezas de esos trabajos; y hace falta nombrar, poner palabras y condiciones materiales y simbólicas para hacerlos vivibles; vertebrar todo un sistema jurídico, político, económico, para que los cuidados no se sigan acumulando en los mismos cuerpos precarizados, sometidos a condiciones de esclavitud y de enfermedad. Estas jornadas, sin duda, han arrojado luz a ese cajón, y cada voz, cada cuerpo, desde su especificidad irreductible, ha ayudado a convertir esa maraña de trabajos invisibilizados en una trama donde cada fibra es discernible, como también lo son las uniones donde estas se entrelazan. No pretendo, en este texto, visibilizar cada una de esas fibras y uniones, no puedo hacer una traducción literal de lo que allí sucedió. No puedo mostrar tanto porque tengo que mostrar algo más.

Si no resuelvo la escritura, la postergo, por ejemplo, pintando. Pintar las palabras de las otras ha tenido en este caso una doble función: calmar la ansiedad que me produce trabajar, trabajando. Un globo y un diamante. Durante la primera jornada Irati Mogollón habló de un globo deshinchado para describir algo muy concreto: la forma rara que adquieren algunos movimientos sociales después de haber crecido muy rápido y haber menguado igual de rápido. Irati nos habló de que las alternativas de sostenibilidad de la vida son cotidianas, y del reto que supone eso, ya que después de un tiempo la erótica política se desvanece y la gente pierde interés, motivación, energía, deseo. Postergar es a veces desear hacia otro lado. Mientras pinto pienso también en un cuerpo cansado o enfermo, en un cuerpo que cuida en condiciones precarias porque no le queda otro remedio.

Después viene otra imagen. La del esplendor. Luisa les había pedido a las ponentes de la primera sesión que pensaran sobre las riquezas que generan los cuerpos que cuidan y Erika Irusta imaginó que su cuerpo albergaba unos diamantes, unas riquezas que era incapaz de ver, porque le han robado los ojos, la capacidad de sentirse orgullosa y la posibilidad de dejarlas estar. Y se preguntaba ¿tenemos que extraer nuestras riquezas? ¿La relación con las riquezas en los cuidados tiene que ser siempre extractiva? ¿Tengo que producir con ellas? Para Erika, ‘expoliadora expoliada’, lo que el sistema –blanco-colonial-cisheteropatriarcal– hace con los cuerpos maternos y los cuerpos que cuidan es expoliar sus muchas riquezas, las necesarias para el sostenimiento de la vida y la continuidad del propio sistema.

III

Junio de 2020

“Para el tiempo que me queda, no me compensa el silencio”

Me compré un bastón. Lo hice porque me costaba caminar. Lo necesitaba para cualquier distancia de más de 100m, para subir y bajar las escaleras de casa.

Al principio también me agarraba fuerte a la superficie de la mesa para poder levantarme del sofá. Me apoyaba en las paredes para descargar el peso de la cadera enferma.

Esto sucedió un poco antes y un poco después del diagnóstico: Mi cáncer de mama de hace justo once años, ha hecho metástasis en mis huesos. Hay afectación en vértebras, costillas y pelvis.

El cáncer ha vuelto, esta vez para quedarse.

De repente anoche, otra vez insomnio, me pareció que le tenía que declarar la guerra, o no, más bien abandonar a su desidia al silencio, al bloqueo que me impide escribir desde hace tanto tiempo. Sea lo que sea que tenga que decir.

Por ejemplo: la vida y el cáncer terminan en el mismo punto.

*

Transcribo las palabras de mi madre, también. Las he sacado de un cuaderno con cubierta verde y páginas amarillas titulado ‘Crónica del cáncer’. Mi madre siempre había escrito diarios, pero para entonces llevaba bastante tiempo sin hacerlo. Se había dado cuenta de que había estado aplicando una sutil autocensura a todo lo escrito –un sustrato de pudor monjil limpiándolo todo, abrillantando hasta los huecos más profundos– y entonces había decidido dejar de escribir. Sin embargo, volver a enfermar y releer Los diarios del cáncer de Audre Lorde le hizo retomarlo.

Poco tiempo después el cáncer avanzó hasta su médula espinal, arrebatándole la movilidad y la sensibilidad de cintura para abajo. La ingresaron en la unidad de urgencias oncológicas y la trataron con radioterapia, además de con quimioterapia. Más tarde la trasladaron a cuidados paliativos hasta que pudo volver a casa, donde murió en la madrugada del 27 de enero de 2021.

Me dejó en herencia sus palabras, esparcidas en un montón de diarios.

*

Intuyo que de este cuaderno no va a salir ninguna reflexión especialmente interesante, ni que no haya sido expresada ya.

Sin embargo no por ello voy a continuar en silencio. Es importante que me diga a mí misma lo que no cabe habitualmente en las conversaciones cotidianas, con familia o amigxs que desmonte la apariencia de normalidad por la que cada día pago un precio.

*

Tampoco son iguales los silencios. El de Audre Lorde, mujer negra, poeta, feminista, madre, lesbiana, amante, guerrera, es mucho más urgente de volcar en palabras que el mío: mujer blanca, heterosexual, normativa, superviviente de muchas guerras, grandes y pequeñas… Ella dice: “Y, por supuesto, tengo miedo porque la transformación del silencio en lenguaje y acción es un acto de auto-revelación y eso siempre parece cargado de peligro”.

“Podemos quedarnos en nuestros seguros rincones mudas como botellas y, aun así, nuestro miedo no se achicará”.

Ella eligió el activismo como compromiso con el lenguaje. Yo soy una botella muda. Muda e inconsciente, porque quizás he sepultado mis miedos para que no me revelen nada incómodo.

Estoy cansada.

*

Octubre de 2020

Llevaba varios días ya oliendo a cloaca.

La dichosa bolsa del pis, con los tubos bien llenos de sedimentos, me tenían el olfato amargado. Por fin me la han cambiado esta tarde ¡Qué descanso! ¡No sé qué somos por dentro, pero no es para hacerse muchas ilusiones!

Escribo a pulso. Ya no sé ni cómo poner el cuaderno. No hay manera de coger una postura normal para escribir en la cama en este cuaderno blando que se me escurre todo.

*

Es muy básico: si el cuerpo está débil, el ánimo cae.

Yo me resisto hasta a esa premisa tan sencilla. Siempre quiero estar fuerte, siempre quiero estar bien. Me cuesta mucho aceptar estos momentos de debilidad y apatía.

Los últimos días sentía que tocaba fondo: sin ganas de nada, preocupada hasta porque iban a venir a cuidarme las amigas, incapaz de relajarme, qué ratos más malos he pasado. Lo confieso abiertamente: lo he pasado realmente mal, al punto de dudar, de perder la confianza en el proceso…

*

Noviembre de 2020

Solo agradecimiento, siempre, a pesar del confinamiento de la habitación y los inconvenientes de estar hospitalizada. El que más me pesaba era una sensación de claustrofobia, como digo, y tristeza que me iba empapando un poco más cada día. Ya no me aliviaba ni mirar los dibujos, ni las flores… solo quería salir de allí. Quizás eso pueda interpretarse como señal de recuperación. No lo sé. Es verdad que al final he estado más fuerte. Y que ahora agradezco mucho pasar la postquimio en casa.

*

Mientras, mi rutina no ha variado mucho. Seguir asimilando la discapacidad, fundamentalmente, con todas las limitaciones que me acarrea y con la constatación, a su vez, del enorme cariño con que estoy siendo tratada. Con el inmenso regalo del amor de los míos y los cercanos.

*

Enero de 2021

Cada día me cuesta más escribir.

*

Me cuesta escribir pero tampoco me compensa el silencio. Interrogo mi malestar para nombrarlo. Si digo ansiedad abro otro cajón de sastre sin una luz con que alumbrarlo. Tampoco lo llamo depresión porque me deshice del marco productivo frente al que mirarlo. Es un malestar ordinario y generalizado que no sé dónde situar, si dentro o fuera del cuerpo. Pienso que debe estar en un espacio liminal, intersticial y móvil, porque cuando creo haberlo identificado se disuelve y se escapa, y me deja informe y sin esplendor. Puede que tenga que ver con el duelo, o puede que no.

Había algo muy gratificante en cuidar. Sin duda, acompañar el proceso de enfermedad y muerte de mi madre ha sido mi privilegio. La forma de autocuidado más urgente. Y aun así, han sido necesarios muchos cuerpos más, dinero y tiempo para hacer el proceso vivible y digno. En mi caso, acabé abandonando el trabajo que me proporcionaba ingresos regulares. Eché de menos un sostén social, uno que no pasase por la institución médica, porque necesitar cuidar de alguien no es una enfermedad. Eché de menos que los trámites para las ayudas a la dependencia fuesen más cortos, ya que no llegaron a tiempo. Tengo claro que hubo dificultades evitables. Y me gustaría haber tenido una alternativa a dejar mi trabajo, o una alternativa a la culpa por no poder con todo.

Pero cuidar ha sido mi privilegio. Solo tengo agradecimiento hacia los cuerpos que nos han acompañado en este proceso, tan bello y duro al mismo tiempo, y sobre todo hacia mi madre, Carmen, quien (me) cuidó durante toda su vida y hasta el último día, haciendo que cuidarla fuese un placer.

IV

Acompañar.

Escuchar.

Estar presente.

Vaciar la bolsa del pis.

Cambiar el pañal.

Asear un cuerpo que no puede moverse.

Vestirlo.

Hidratarlo.

Manejar una grúa para trasladarlo.

Masajear unos pies que no sienten.

Ser dedos tecleadores que transcriben.

Ser sus piernas.

Limpiar debajo de la cama.

Limpiar alrededor.

Sujetar la cuchara.

Besar un cuerpo amado.

Besar un cuerpo que muere.

Inyectarle morfina. midazolam. haloperidol.

Sujetar la mano.

Acariciar la mano.

Soltar la mano.

Abrazar un cuerpo amado muerto.

V

…

Devolverle la dignidad y el valor al trabajo de cuidados.

Escribir el Estatuto de los Cuidados.

Modificar la Ley de Dependencia.

Derogar la Ley de Extranjería.

Abolir el trabajo de interna.

Acabar con los abusos y las agresiones racistas dentro de los hogares españoles.

Diferenciar el trabajo de hogar del trabajo de cuidados.

Redactar una ley específica para el trabajo de cuidados de personas dependientes en los hogares.

Garantizar el derecho de las personas dependientes a decidir cómo quieren ser cuidadas.

Restituir el expolio materno.

Garantizar el soporte psicoafectivo durante el puerperio.

Enmendar el expolio a los cuerpos migrados.

Crear una trama urbana a partir de los cuerpos que cuidan y de los cuerpos que necesitan ser cuidados.

Implantar la Renta Básica Universal.

Remunerar los cuidados.

Ampliar los permisos para cuidar de personas dependientes y con enfermedades terminales.

Ampliar los permisos por muerte de un ser querido. Garantizar el derecho al duelo.

Politizar el malestar. Despatologizarlo.

Reducir la burocracia.

Trabajar las narrativas épicas cotidianas.

Situar los límites del sostenimiento de la vida.

Trabajar la reciprocidad feminista.

Acuerpar las luchas de todas.

…

Gracias a Luisa, Irati, Erika, María, Irene, Sarah, Mary, Ana, Alexia, Cristina, Gabriela, Paloma, Blanca, Zarys, Lara, Anita y muchas más, por no conformaros con el silencio.

Downloads